Nobusuke Kishi became the leader of the rising conservative movement in Japan. Within a year of his election to the Diet, using Kodama's money and his own considerable political skills, he controlled the largest faction among Japan's elected representives. Once in office, he built the ruling party that led the nation for nearly half a century.

He had signed the declaration of war against the United States in 1941 and led Japan's munitions ministry during World War II. Even while imprisoned after the war, Kishi had well-placed allies in the United States, among them Joseph Grew, the American ambassador in Tokyo when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Grew was under detention in Tokyo in 1942 when Kishi, as a member of the war cabinet, offered to let him out to play a round of golf. They became friends. Days after Kishi was freed from prison, Grew became the first chairman of the National Committee for a Free Europe, the CIA front created to support Radio Free Europe and other political-warfare programs. [...]

In May 1954, he staged a political coming-out at the Kabuki Theater in Tokyo. He invited Bill Hutchinson, an OSS veteran who worked with the CIA in Japan as an information and propaganda officer at the American embassy, to attend the theater with him. He paraded Hutchinson around the ornate foyers of the Kabuki-za at intermission, showing him off to his friends among the Japanese elite. It was a highly unusual gesture at the time, but it was pure political theater, Kishi's way of announcing in public that he was back in the international arena-and in the good graces of the United States.

For a year, Kishi met in secret with CIA and State Department officials in Hutchinson's living room. "It was clear that he wanted at least the tacit backing of the United States government," Hutchinson remembered. The talks laid the groundwork for the next forty years of Japan's relations with the United States.

Kishi told the Americans that his strategy was to wreck the ruling Liberal Party, rename it, rebuild it, and run it. The new Liberal Democratic Party under his command would be neither liberal nor democratic, but a right-wing club of feudal leaders rising from the ashes of imperial Japan. [...] He pledged to change the foreign policies of Japan to fit American desires. The United States could keep its military bases in Japan and store nuclear weapons there, a matter of some sensitivity in Japan. All he asked in return was secret political support from America.

The most crucial interaction between the CIA and the Liberal Democratic Party was the exchange of information for money. It was used to support the party and to recruit informers within it. The Americans established paid relationships with promising young men who became, a generation later, members of parliament, ministers, and elder statesmen. Together they promoted the LDP and subverted Japan's Socialist Party and labor unions. When it came to bankrolling foreign politicians, the agency had grown more sophisticated than it had been seven years earlier in Italy. Instead of passing suitcases filled with cash in four-star hotels, the CIA used trusted American businessmen as go-betweens to deliver money to benefit its allies. Among these were executives from Lockheed, the aircraft company then building the U-2 and negotiating to sell warplanes to the new Japanese defense forces Kishi aimed to build.

In November 1955, Kishi unified Japan's conservatives under the banner of the Liberal Democratic Party. As the party's leader, he allowed the CIA to recruit and run his political followers on a seat-by-seat basis in the Japanese parliament. As he maneuvered his way to the top, he pledged to work with the agency in reshaping a new security treaty between the United States and Japan. As Kishi's case officer, the CIA's Clyde McAvoy was able to report on-and influence-the emerging foreign policy of postwar Japan. [...]

President Eisenhower himself decided that Japanese political support for the security treaty and American financial support for Kishi were one and the same. He authorized a continuing series of CIA payoffs to key members of the LDP. Politicians unwitting of the CIA's role were told that the money came from the titans of corporate America. The money flowed for at least fifteen years, under four American presidents, and it helped consolidate one-party rule in Japan for the rest of the cold war.

Others followed in Kishi's path. Okinori Kaya had been the finance minister in Japan's wartime cabinet. Convicted as a war criminal, he was sentenced to life in prison. Paroled in 1955 and pardoned in 1957, he became one of Kishi's closest advisers and a key member of the LDP's internal security committee.

Kaya became a recruited agent of the CIA either immediately before or immediately after he was elected to the Diet in 1958. After his recruitment, he wanted to travel to the United States and meet Allen Dulles in person. The CIA, skittish about the appearance of a convicted war criminal meeting with the director of central intelligence, kept the meeting secret for nearly fifty years. But on February 6, 1959, Kaya came to visit Dulles at CIA headquarters and asked the director to enter into a formal agreement to share intelligence with his internal security committee. "Everyone agreed that cooperation between CIA and the Japanese regarding countersubversion was most desirable and that the subject was one of major interest to CIA," say the minutes of their talk. Dulles regarded Kaya as his agent, and six months later he wrote him to say: "I am most interested in learning your views both in international affairs affecting relations between our countries and on the situation within Japan."

Kaya's on-and-off relationship with the CIA reached a peak in 1968, when he was the leading political adviser to Prime Minister Eisaku Sato. The biggest domestic political issue in Japan that year was the enormous American military base on Okinawa, a crucial staging ground for the bombing of Vietnam and a storehouse of American nuclear weapons. Okinawa was under American control, but regional elections were set for November 10, and opposition politicians threatened to force the United States off the island. Kaya played a key role in the CIA's covert actions aimed to swing the elections for the LDP, which narrowly failed. Okinawa itself returned to Japanese administration in 1972, but the American military remains there to this day.

The Japanese came to describe the political system created with the CIA's support as kozo oshoku-"structural corruption." The CIA's payoffs went on into the 1970s. The structural corruption of the political life of Japan continued

-- Tim Weiner, Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA

Nobosuke Kishi, a gangster in the narcotics business who was actively involved in the use of slave labor as a wartime minister in the Japanese cabinet, likewise remains happily unprosecuted.

The only expert on international law on the Tokyo war crimes court, Radhabinod Pal of India, calls the whole sorry farce "an ethical travesty" but not too many newspaper readers in the U.S. find out about it.

After the execution of those defendants sentenced to death, General Douglas MacArthur releases the remainder of those few "Class A" war criminals who have been prosecuted and convicted. Like the thousands of unprosecuted war criminals, these mass murderers and torturers slide easily into positions of power in MacArthur's America-compliant post-war Japan in politics, business, the civil service and academia. Leading the pack is Nobusuke Kishi, who will become Prime Minister of Japan in 1957, his "election" bought and paid for by the CIA with loot stolen from the victims of Japan's war criminals.

Kishi (indicated by circle) as a newly appointed member of the war cabinet of Prime Minister Tojo Hideki, October 1941. He served as minister of commerce and industry until the end of the war in 1945.

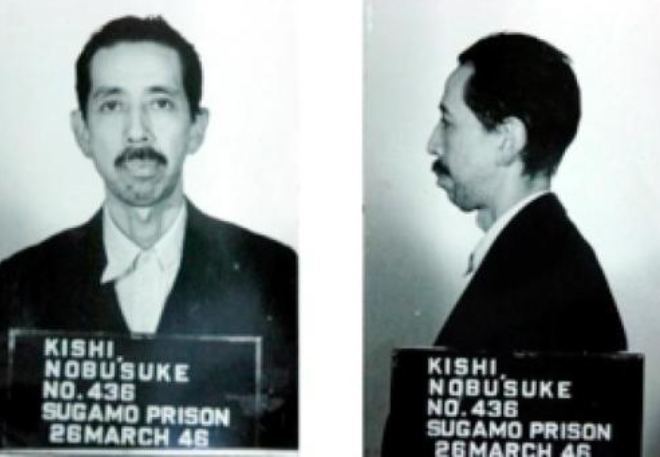

Kishi's "mug shot" after he was arrested by U.S. occupation authorities and incarcerated in Sugamo Prison along with other accused and indicted Japanese war criminals.

Shinzo Abe prays before the grave of his grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, a former prime minister, on Dec. 22 in Tabuse, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Standing behind him are his wife, Akie, and brother Nobuo Kishi.